Hat tip: JFK researcher Will Hart provided all of the research for this article. He kindly sent me primary documents and put together an excellent chronology of events. Will also sent me links to the various mentions of the Ralph Yates story in conspiracy books, articles and podcasts. Thank you very much, Will.

When the twenty-six volumes of the Warren Report were released in 1964, researchers were able to find a treasure chest of conspiracy stories. The FBI had investigated all sorts of stories which made their way into the 1,550 Warren Commission documents. Some of these were then included in the twenty-six volumes.

A good example is the story of Nancy Perrin Rich, who testified before the Warren Commission that she saw Jack Ruby at a meeting to discuss gun running into Cuba. Mark Lane gave her story an entire chapter in his book, Rush to Judgment. But if you actually read her testimony, you will be struck by her inability to answer questions - I actually started laughing when I read her testimony.

Some Warren Commission critics would find stories they felt deserved further investigation, For instance, Gary Schoener spent a lot of time researching a story in Martinsburg, Pennsylvania. A woman claimed to have found a piece of trash from a neighbor with the names of Rubinstein and Lee Oswald. There was nothing to the story, but you will still find it in conspiracy books such as James DiEugenio's Destiny Betrayed.

Another story was that of Lloyd John Wilson, a young man who claimed that, at a wrestling match in San Francisco, he paid Lee Harvey Oswald $1,000 to kill JFK. The FBI investigated this back in 1963-1964 and found it baseless. The story has since been resuscitated by Vince Palamara in his book The Plot to Kill President Kennedy in Chicago.

The story of Ralph Yates is another story that has been resuscitated. It was not included in the twenty-six volumes, so the early critics missed the story. But once the critics started examining the Warren Commission documents, it was found, and Sylvia Meagher was the first to find it. She wrote about it in an unpublished essay in 1970 which was finally published in 1986:

But as Meagher notes, Oswald was in the Texas School Book Depository on 10:00 AM on November 21st. So, the hitchhiker could not have been Oswald:

So, what is really going on here?

Let's have a look at the entire story and its evolution through the conspiracy literature.

November 26, 1963: Yates appears at the FBI office in Dallas to tell his story about the hitchhiker:

Yates identified the man as Lee Harvey Oswald. He told a co-worker about what had happened:

The whole story, on its face, is preposterous.

November 27, 1963: The FBI speaks with Dempsey Jones. Right off the bat, we have a clue. Jones tells the FBI that "YATES is a big talker who always talks about a lot of foolishness."

So, "YATES did not discuss this man the day before the President was shot in any great detail."

But there is another clue here -- " ... YATES said this man told him it was some window shades he was carrying for the company he (the man) had made."

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram mentioned a man who drove Oswald to the TSBD and that Oswald told him his package contained window shades in a page one story on November 24, 1963:

So, there are two conversations here. The first one took place before the assassination and was quite general, and then more specifics were added after the assassination.

Here is a summary of their two conversations:

First conversation: Yates picked up a boy hitchhiking who had a package. This man discussed that "one could be in a building and shoot the president." Yates offered few details about the man.

Second conversation: After the assassination, Yates described the package as long and that it contained window shades. Now the man he had picked up was Lee Harvey Oswald.

Of course, Jones' distinction between what Yates said "on the first date" and on the second is an unreliable recollection.

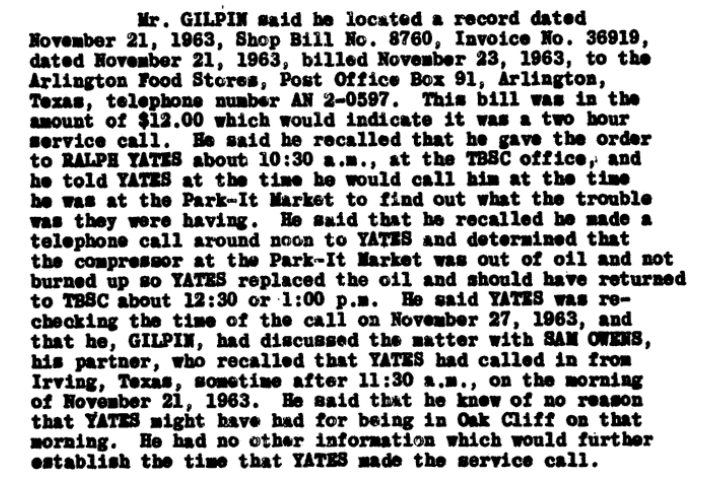

November 27, 1963: The FBI interviews J. R. Gilpin, one of the partners in the company that Ralph Yates worked for.

Gilpin said "that he knew of no reason that YATES might have had for being in Oak Cliff on that morning."

December 6, 1963: Airtel from FBIHQ to the Dallas office.

The FBIHQ reviewer did not think that Yates was being truthful and suggested obtaining a signed statement and a polygraph examination.

December 10, 1963: The FBI obtained a signed statement from Ralph Yates.

Now Yates talks about Jack Rubenstein. In his first interview, he did not remember the name of the man associated with the Carousel Club:

Yates also said that he was watching television and reading newspapers after the assassination:

Yates also told the FBI that he had been treated for a "nervous condition":

December 10, 1963: Consent for a polygraph:

January 2, 1964: Teletype to SAC Dallas from from Director Hoover's office:

January 3, 1964: Interview of Ralph Yates:

Yates tell the FBI that the reason he was at Charlie's Meat Market was to pick up a check.

January 3, 1964: Interview of Thomas Ayres, an employee at Charlies Meat Market:

Thomas Ayres tells the FBI that he does not recall giving a check to an employee of the Butcher company.

January 3, 1964: Interview of Donald Mask, an employee at Charlie's Meat Market:

Donald Mask tells the FBI that he not recall giving a check to an employee of the Butcher Company.

January 4, 1964: Statement of Ralph Yates

Besides changing his entire story, Yates now says that he had the same conversation with the hitchhiker that he had previously with Jones -- "that a man could be shot from a window or building top ..."

January 8, 1964: Results of Polygraph Test

The polygraph test was inconclusive.

January 8, 1964: Yates telephones the FBI.

January 9, 1964: Yates goes to the FBI.

Yates says that "everything he previously reported seemed unreal to him, as if he had dreamed it ..." In addition, there is a history of mental illness in the Yates family.

January 9, 1964: The FBI interviews Mrs. Yates:

Mrs. Yates told the FBI that "he mentioned nothing about this to her, until after everything he told that indicated he had picked up Lee Harvey Oswald had appeared in the newspapers and television." She is also "concerned about his mental condition."

January 15, 1964: Mr. and Mrs. Yates visit the FBI.

Ralph Yates tells the FBI that "his doctors were trying to kill him."

Well, what can you say? Yates was right be afraid that he was losing his mind.

January 16, 1964: Call from Mrs. Yates to the FBI.

The date in this report is wrong. She called on January 16th, but must be referring to her husband's visit on January 15th.

January 22, 1964: Second FBI Gemberling Report, CD 329.

That's the entire Ralph Yates story, and it's a sad one.

You would think that conspiracy theorists wouldn't be interested in this story. It doesn't quite fit into any conceivable narrative, and it is pretty clear that Mr. Yates was a disturbed man.

And yet Sylvia Meagher thought it worthwhile to write about, largely because she thought that there were some leads apparently worth pursuing in the unpublished Warren Commission documents. Regarding Yates, Meagher only mentioned two possibilities -- deliberate fraud and truthfulness. She did not have the follow-up material from CD 329 that would have led her to the conclusion that Yates was a disturbed man.

Meagher also wondered if some of the information that Yates gave to the FBI was already in the public domain. The editor of The Third Decade wrote this note:

In recent correspondence Meagher has pointed out that NBC news broadcasts of 11/23 and 11/24 refer to Oswald having brought the rifle to work in a package and of his having told a neighbor that the package contained "windows blinds." Whether the details of the "backyard photographs" corresponding to the photograph shown to Yates by "Oswald" were similarly matters of "public domain" knowledge is not too certain at this time.

We have already shown that "window shades" was in the public domain (see above).

In this November 1963 clip, Chief Curry describes the photographs: (5:26:11)

Here is Meagher's conclusion to her article:

Whether the story was true in essence, or whether Yates and Jones conspired in a falsification -- out of sheer malice and mischief? to bolster the case against Oswald at a moment when the evidence seemed dubious and was being sharply questioned? -- the matter raises questions of first importance. The shadow of a dual "Oswald" has not been dispelled.

The Editor of The Third Decade, Professor Jerry Rose, attached a note to Meagher's article in which he thought that "Many other of the "Second Oswald" sightings might be examined from the same perspective of suspicion that they were post-assassination efforts, instigated by the FBI, to develop pre-assassination incriminations of Oswald."

The possibility that Yates was just a disturbed young man who could not distinguish dream-like fantasies from reality was not considered for some reason.

Yet another indication that someone is impersonating Oswald and discussing the President's visit, only two days before the assassination.

But Armstrong does not include the statements of J. R. Gilpin, Thomas Ayres, and Donald Mask, who all say that Yates had no reason to be in Oak Cliff. Armstrong says nothing about Yates' mental issues.

James Douglass included the story in his 2008 book JFK and the Unspeakable. Douglass writes that "the FBI was not happy with the statement of Ralph Leon Yates," and that "they kept recalling him in order to discredit his story." But this is not true - Yates had seven total contacts with the FBI and he initiated four of them.

Douglass spoke to Yates's wife, Dorothy: (page 354)

In an interview forty-two years later, she told me what happened next to her husband. After he completed his (inconclusive) lie-detector test, she said, the FBI told him he needed to go immediately to Woodlawn Hospital, the Dallas hospital for the mentally ill. He drove there with Dorothy. He was admitted that evening as a psychiatric patient. From that point on, he spent the remaining eleven years of his life as a patient in and out of mental health hospitals.

Douglass tries to convince his readers that the FBI was responsible for Yates's mental break and that they were the ones who insisted he go to the psychiatric hospital: (page 354)

The wrenching but undeniable truth for Yates, that he helped a man he thought was the president's assassin deliver what could have been his weapon to the Book Depository, was what compelled him to contact the FBI in the first place. Now he was being told his experience was nothing but an illusion. The FBI said so. Because of Yates's unswerving, polygraphed conviction to the contrary, that he knew what really happened. J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI knew what they had to do. They told him to report at once to a psychiatric hospital.

But Yates's wife told the FBI that she took her husband to Parkland Hospital, and after conferring with doctors there, he was accepted at Woodlawn Hospital.

Her husband spiraled downward: (page 354 - 355)

She does know that early one morning about a week later, Ralph broke out of Woodlawn. At 4:00 A.M. she opened the front door of their house to find Ralph standing barefoot on the steps in his white hospital clothes. Snow was swirling around him. Ralph told Dorothy he had escaped from the mental institution. He said he tied sheets together and climbed down from a window. He had then stolen a car and driven home.

Ralph was tormented by fear in a way Dorothy would see repeated for years. He told his wife someone was trying to kill him and their children because of what he knew about Oswald. She quickly bundled up their five sleepy children, the oldest of which was six. Ralph drove his family away from their house in the stolen car. Within a few hours, Dorothy was more alarmed by her husband's frantic efforts to evade their murder at every turn than she was by any unidentified killers. She returned the car and reported his whereabouts to the Woodlawn Hospital authorities.

Ralph was picked up and returned to Woodlawn. He was soon transferred to Terrell State Hospital, a psychiatric facility about thirty miles east of Dallas, where he lived for eight years. He was then transferred to the Veterans Hospital in Waco for a year and half, and finally to Rusk State Hospital for the final year and a half of his life. While a patient at all three hospitals, he spent intermittent periods of from one to three months at home with his wife and children. He was never able to work again.

Interestingly, Douglass also spoke to some of Yates's relatives and friends. His uncle, J. O. Smith, told him that Yates's story "was all just imagination." His cousin said that the episode consumed him: (page 356)

He wouldn't let it go. He believed it to be true. This consumed Ralph. His thinking didn't go beyond that afterwards. This just totally destroyed his life. Ralph blamed himself for Kennedy's assassination. He said, "I was the reason the President got killed."

Rather than admit that Yates was disturbed, Douglass believes the essence of the story: (page 356)

There were too many Oswalds in view, with too many smuggled rifles, retelling a familiar story to too many witnesses. At least one curtain rods story, and the disposable witness who heard it, had to go. The obvious person to be jettisoned was the hapless Ralph Yates. His stubborn insistence on what he knew he had seen and heard, from the man he had given a ride, had to be squelched.

To Douglass, "Ralph Yates was a witness to the unspeakable."

Of course, James DiEugenio devoted a lot of space to the Yates story in his review of JFK and the Unspeakable.

Yates mental-health hospitalization 'was the price for disturbing the equilibrium of the official story.'

Lately, the Ralph Yates story has come back to life.

An episode of the Solving JFK podcast series featured Yates:

The story then got picked up by Barstool Sports, where it made their list of the top unanswered questions about the JFK assassination.

Ralph Lee Yates was a family man with a wife and five kids who had never been in trouble with the law. But he died in a mental institution where he was sent against his will. For the crime of passing lie detector tests ordered by Hoover. Because the Feds argued he must be insane to believe a thing they didn't think was true.

Did all this happen to silence a man whose account might make people believe an Oswald lookalike was sent to Dallas to kill JFK and frame Oswald for it? No one can prove it. But it makes sense. And put this altogether and you've got the all the essential ingredients that makes a crazy theory a legitimate conspiracy.

Ordinarily I wouldn't care about Barstool Sports but their X account has over six million followers.

And not surprisingly, the book Chokeholds includes the Yates story in its chapter, "Oswald was Impersonated":

After the January 4th interview, the FBI told Yates that he had passed the lie detector test because the test showed that Yates believed what he was saying was true. However, because the FBI said that they knew what Yates was saying could not be true, Yates was declared to be mentally insane and needed to immediately check in to a mental institution.

Not exactly. The polygraph test was inconclusive. The next day, Yates visited the FBI and was emotional and cried through the meeting. Six days later, he came back and said he thought his doctors were trying to kill him. The FBI suggested he seek help at Parkland Hospital. His wife took him there and the doctors had him admitted to Woodlawn.

Chokeholds then adds "when one reads the story of the FBI forcibly committing Yates ..."

Forcibly?

Chokeholds claims the Yates story is a "showstopper," and that "the Feds committed this man to a mental institution without due process all because the told what was apparently an inconvenient truth."

Chokeholds concludes its section on Yates by noting that "Leading Warren Report defenders do not have a substantive counterpoint to the story of Ralph Yates."

Really?

We have now had over sixty years of experience in understanding JFK assassination witnesses. Some dissemble quite obviously like Judyth Vary Baker and Beverly Oliver. Others suffered from organic brain damage like Richard Case Nagell, or some mental illness like Raymond Broshears. We should be able to use our current experience to look back at witnesses like Ralph Yates. He was a disturbed man who confused real events with imaginary ones.

You would think that this story would disappear over time. It's a sign of the ever-discouraging debate on the JFK assassination that the Ralph Yates story is actually gaining traction.

Like Roger Craig, Ralph Yates let conspiracy fever drive him crazy. He died of congestive heart failure on September 3, 1975. He was only thirty-nine years old.

An additional thank you to Paul Hoch who reviewed this article and made many important suggestions for improvement.

Previous Relevant Blog Posts

A fictitious story about Larry Crafard found its way into the book.

Chokeholds leaves out a lot of information about Aloysius Habighorst.

Bleau doesn't tell his readers about Roger Craig's credibility problems.

Bleau believes the Rose Cherami story.

Bleau claims the Shaw jury believed there was a conspiracy in the JFK assassination. This is just not true.

Bleau doesn't tell you everything about Lyndon Johnson's feelings towards the Warren Report.

Bleau leaves out some important details about the beliefs of Burt Griffin.

Bleau leaves out an important paragraph from Alfredda Scobey's article on the Warren Commission.

Bleau misleads readers on the testimony of John Moss Whitten.

Bleau gets it all wrong on Dr. George Burkley.

Bleau doesn't tell the whole story about John Sherman Cooper.

Bleau claims that J. Lee Rankin questioned the findings of the Warren Report. This is just not true.

Bleau tries to make it appear that Dallas policeman James Leavelle had doubts that Oswald could be found guilty at a trial.

Bleau gets it all wrong on the FBI Summary Report.

Bleau discusses the conclusions of the HSCA but leaves out it most important finding.

Bleau leaves out some important details about a Warren Commission staffer.

Was Oswald a loner? Bleau says no, and then says yes.

Bleau leaves out some important details about Malcolm Kilduff.

An introduction to Paul Bleau's new book, Chokeholds.